Successful vaccine outreach for Hispanics, thanks to strong community-school partnership effort

By Aïda Rogers

Download a copy of the story here

Any South Carolina community trying to vaccinate its Hispanic population successfully against the Covid-19 virus can look to Walhalla for a template on what to do right.

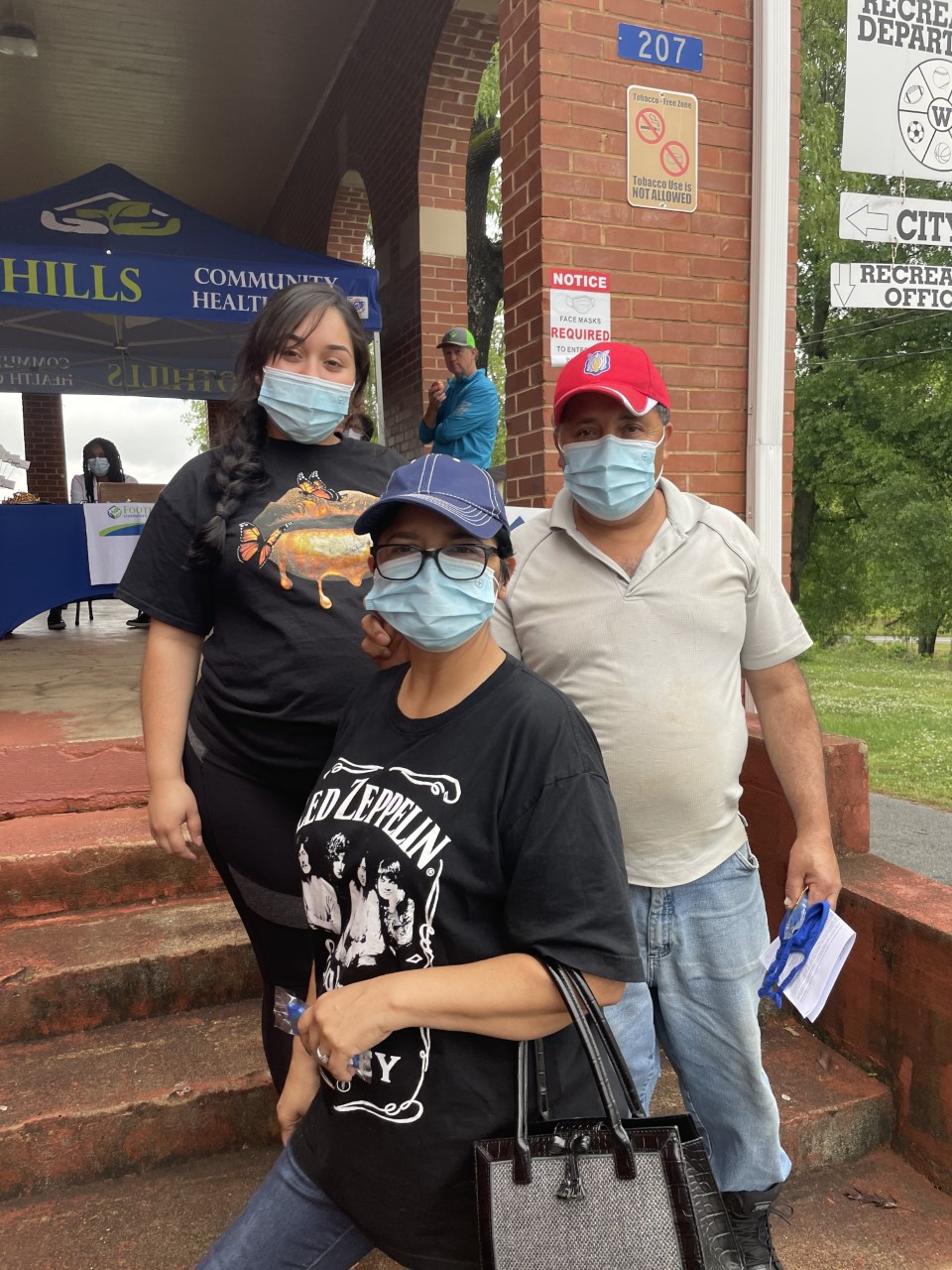

“We met them where they were, literally and physically,” said Sarai Melendez, one of two employees at James M. Brown Elementary School who spearheaded efforts to get non-English-speaking community members vaccinated. She and Family Engagement Liaison Nivia Miranda made sure as many Hispanic community members as possible could receive their first dose when the SC Department of Health and Environmental Control held a pop-up clinic May 3.

Here’s some of what they did:

- Made sure the clinic was in a central, walkable location – in Walhalla’s case, the city’s recreational basketball gym

- Offered reasonable hours for people to get vaccinated. They chose from 1 to 7 p.m., knowing most would be coming late in the day, after work

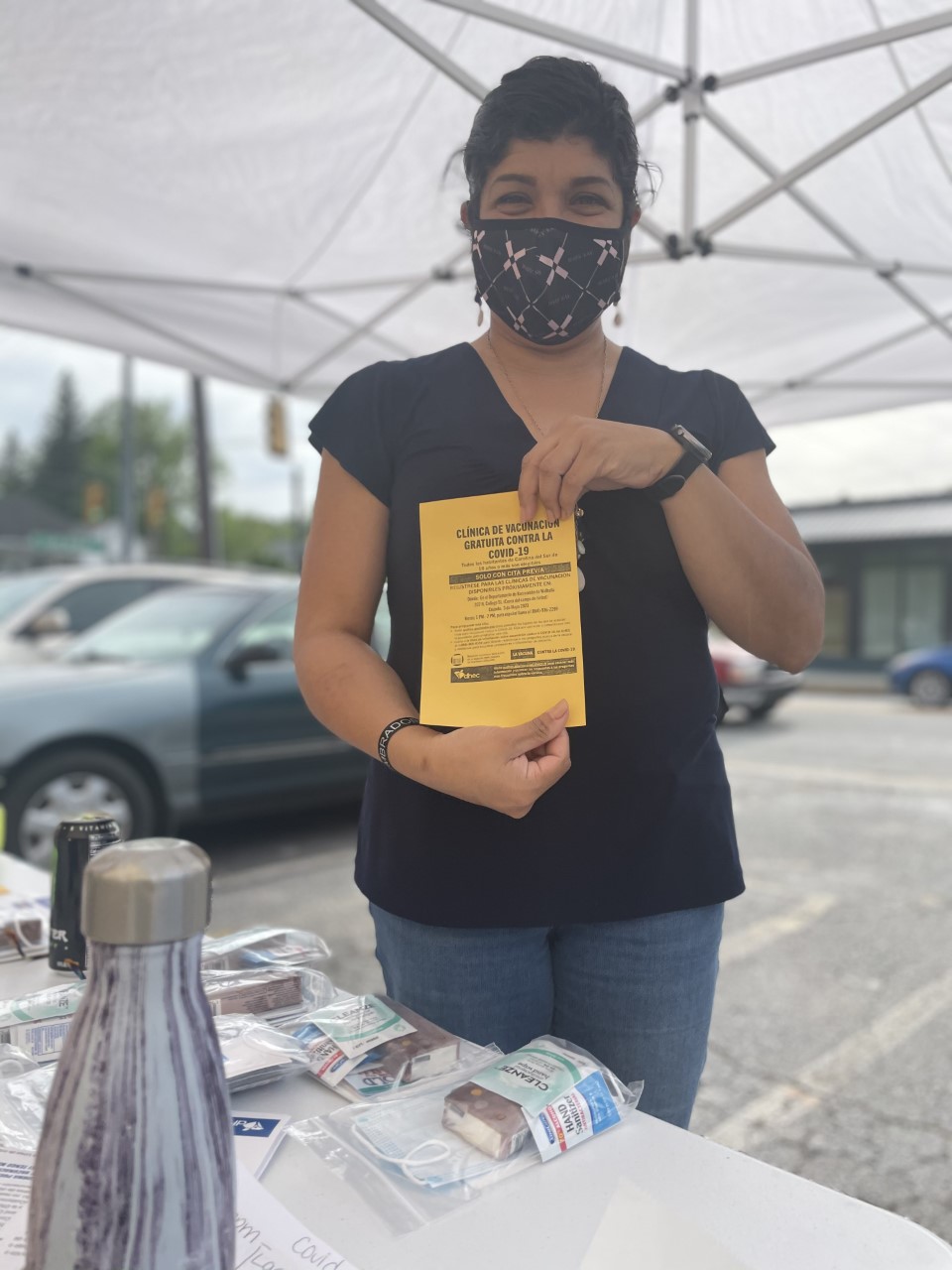

- Created fliers in Spanish about the clinic for Walhalla students to take to their families and to be posted at local tiendas

- Included Melendez’ phone number on the fliers. As a Walhalla city council member, Melendez has a city phone with an 864 area code. She knew this constituency would be comfortable using a local phone number. A number that connects to a digital voice message can be intimidating

- Included specifics about where the vaccines would be given on the fliers. That meant more than a street address. It meant “next to the soccer field,” in Spanish

- Used the telephone. Melendez and Miranda, both fluent in Spanish, called people and had lengthy, detailed conversations about the vaccine and how to get it. They estimate they made 100 phone calls between them

- Made vaccine appointments with pencil and paper, understanding technology can be intimidating, and knowing a scheduled appointment would hold patients accountable

- Made sure patients understood they wouldn’t need an insurance or Social Security card to get the vaccine – very important to someone reluctant to take it

The pair worked the crowd – standing outside a popular tienda the Friday afternoon before the Monday vaccine day, handing out fliers and talking up the clinic. They knew that particular tienda drew a crowd on Friday. When people asked where the vaccine site would be, they would direct them physically to a place on the street and point.

Melendez and Miranda had plenty of community involvement. State Rep. Thomas Alexander contacted Melendez early in 2021, asking for advice on helping vaccinate the Hispanic and African American communities in Walhalla. Besides attending a meeting of the Healthy Oconee Health Disparities Committee, a key player in the effort, he also visited Walhalla on the day of the pop-up clinic to show his support for equitable access to the vaccine.

Bilingual healthcare workers from the Foothills Community Health Center greeted patients, to answer questions and reassure them about the vaccine.

“We found that our Hispanic residents were reluctant and distrustful of the vaccine, but having the individual trusted community members at a trusted community site encouraging them to sign up and alleviating their fears made a significant difference,” said Dr. Lorilei Swanson, CFEC’s Upstate Regional Family Engagement Liaison. She, Melendez, Miranda, and others gave out fliers and flu kits with masks, Kleenex, hand sanitizer, and information about staying healthy at local tiendas.

Having local health center workers staff the event may yield other positive consequences, Swanson said. “They shared information about the health center so Hispanic residents can get connected to medical services from a primary care provider.”

Individual volunteers and other organizations jumped in, including the City of Walhalla’s Diversity and Inclusion Committee and staffers at the Walhalla Public Library, who made copies of the fliers and posted them. In Walhalla, 27 percent of the population is Hispanic.

Of the 110 vaccines DHEC had to distribute that day, 95 percent were used, the agency reported. That translates to 67 people, a much higher number than other towns and cities have managed with their Hispanic communities.

“We would like to have gotten 110 people vaccinated, but at least we got 67 people who never would have been vaccinated because they work 12-hour days,” Miranda said. “They leave the house at 7 and don’t get home until 7 or 8, and they don’t watch the news.”

Those patients received their second doses June 3. Meanwhile, there’s talk of another vaccine day for Hispanic residents. Already those who’ve gotten their first dose are spreading the word to their friends and family.

It’s important for people to understand that language isn’t the only barrier between Hispanics and English speakers, Miranda and Melendez say. Transportation and technology are other difficulties.

That’s why using clipboards instead of smartphones and laptops worked better for this constituency. And Melendez knew to put several chairs together in the gym for family groups to be together, and rest after work.

As Swanson put it, the hard work of many culminated in a “welcoming” atmosphere that helped make Walhalla healthier.

“This was a very purposeful project that took months in the making,” Swanson reflected. “In essence, it was the intentional setting up of the conditions required for trust in the Hispanic community that made this project a success.”